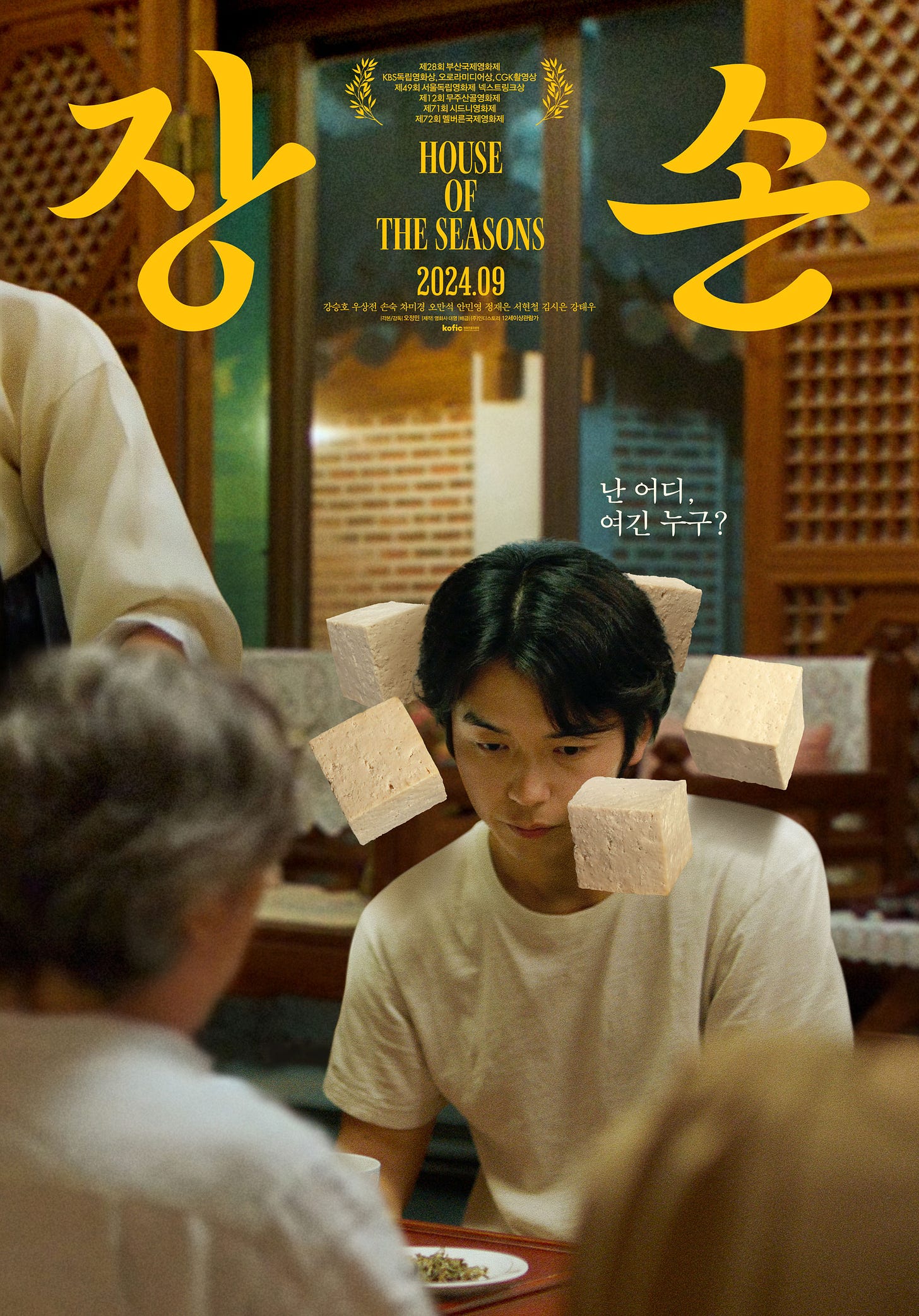

VIFF 2024 Review: House of the Seasons

House of the Seasons, dir. Jung Min-Oh, is a great, beautiful, feeling comedy. I am not sure it is intended as a comedy — in fact, I am pretty sure it is not intended as one. But like Succession — the ultra-successful TV series — the only way you could explain its profound moral impact is via the comedic medium. This is because unlike tragedies — which derive their power from the collision of inevitable circumstances — comedies allow for profound moral lessons to be imparted in a refreshing, non-oleaginous way — via artifice. If the director (thank you!) has read thus far, I hope you excuse my comparison because I think it’s the only way I could do justice to the moral weight of the movie. The storytelling begins when the family gathers — and the younger generations return — to perform the annual ancestral rites. That was in mid-winter. It ends in mid-summer, with the promise — nay, the ineluctability — of spring. The whole thing is phenomenal. The context is a provincial Korean tofu-making family, but the lessons — the hurt, the pain, and then finally the laughter — are universal. It turns out that the ancestral rites have something to teach us after all — not the dry moral didacticisms, but something way more profound and powerful: the ability to navigate modern (and ancient) hypocrisies.

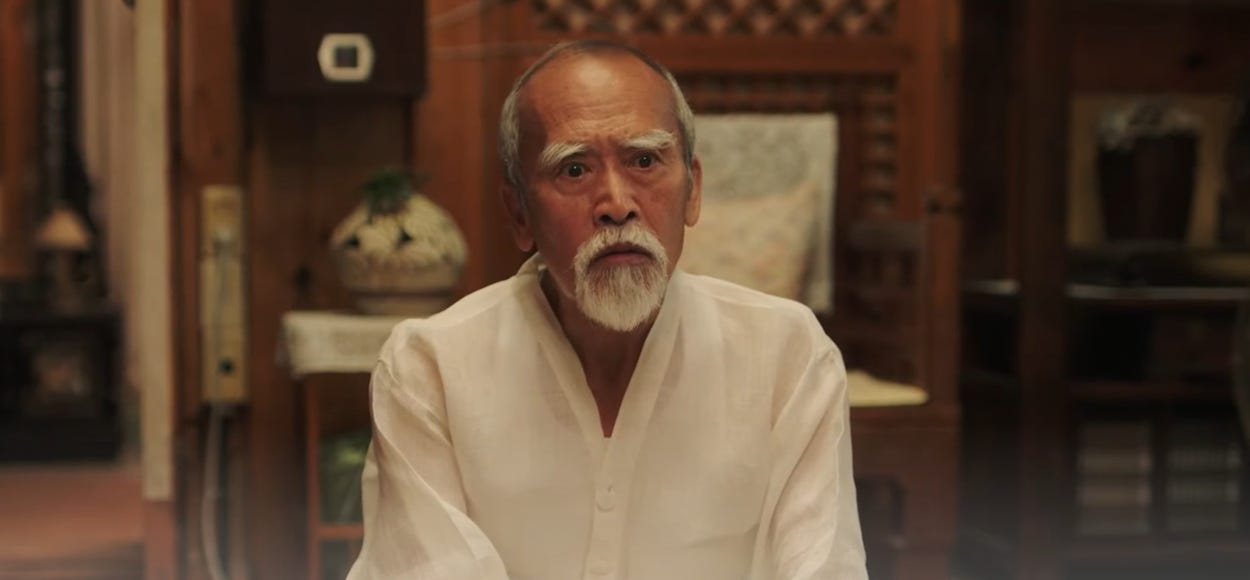

We start with Grandpa, the archetypically stern patriarch of the family. Now (semi-) retired, he spends most of his time wandering around and reading the Confucian classics, insisting on upholding the rites the “correct” way. So far, so lame.

We then meet Seong-jin, the Grandson. He is a struggling actor in Seoul who had just paid for a project with his own money (secretly supplemented by family) and previously appeared in a bit role in a soap. Throwing up in the car back to his ancestral village, he is mocked by Dad, whose limp only hides much bigger disappointments in life.

And then there are the women of the family: his long-suffering mother, his sister who’s four months pregnant, his Christian aunt, and most importantly, his doting — but sharp as a tack — grandmother, to whom he’s the apple of the eye.

With the scene thus set, the action begins. It turns out that Seong-jin (the grandson) hasn’t got any money and is in a bit of a pickle. It also turns out that his parents are worried about his career and his grandparents about his marriage prospects. In addition, since he doesn’t want to run the tofu factory, there’s a succession crisis, there being no other suitable (read: male) heirs. In the mean time, his sister — who is producing an heir — is beset by the typical sexism of provincial families. Honestly, sounds like a slapstick comedy about the travails of modern Korea.

But there’s a deeper crisis. It’s not just that the tofu factory will need a new boss sooner or later, it’s also that automation proposed by its current boss — Seong-jin’s dad — will eliminate a long-time family retainer, the factory manager. We also see that one of the one of Seong-jin’s aunts — married to a sleek industrialist driving a Mercedes-Benz, who has deemed China “too expensive,” moving to the capital-friendlier climes of Vietnam — effectively leaving the family due to the move. Meanwhile, Seong-jin’s other aunt — a devout Christian — struggles with penury induced by her husband’s auto accident. Basically, it’s a crisis of an existing social order unwinding — an order that had provided the clan with a roof over their heads, with food and warmth, but is now under threat due to a changing society and economy.

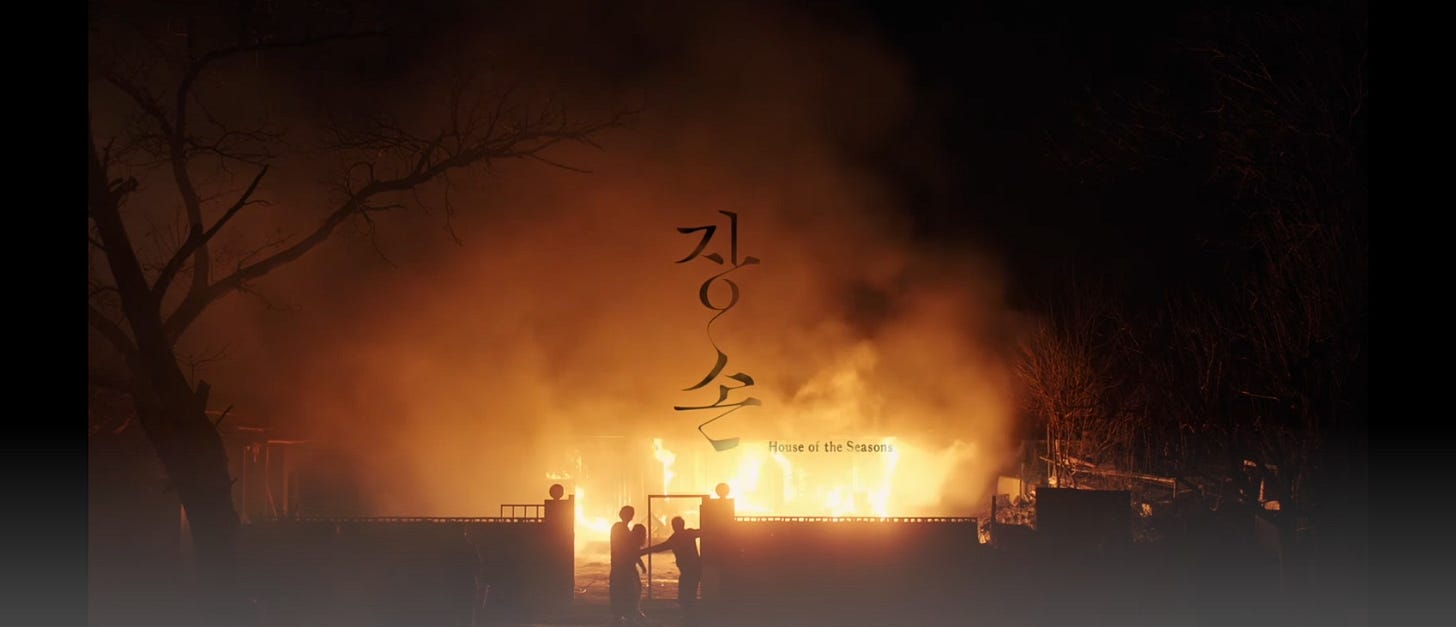

The movie is really about the resolution of this crisis, external and internal, and the way the two come together. The magic of the film, of course, is that the solution isn’t revealed until the very end — when the grandfather revealed to his grandson — or his son? He wasn’t totally lucid — that he “had taken care of everything” and therefore, everyone. At the risk of spoilers, the most important thing he revealed — or rather, the revelation gently suggested — is that he, the elderly, absent-minded white-haired man — was responsible for the fire at the climax of the movie, burning down one of the family residences.

Why? The answer is only hinted at, but it looked like insurance payout for the poor aunt who has been decent and devout without having enough money. Now she will have a nice packet — not enough to live a life of luxury, but a better use of her “shack” surely. In this, I am reminded of an Icelandic TV series — a rather noir drama called Trapped (Ófærð) which I had enjoyed, rather like a warm blanket, at the beginning stages of the pandemmy. In it, the background — or foundational — event is the deliberate burning down of a local fish plant for insurance money against the backdrop of the Global Financial Crisis in ‘08. The fish-plant owner of course justified it on the grounds of necessity for the local economy, but the insurance-adjuster’s daughter — then snooking with her boyfriend at the site — perished. In this version, the fire was portrayed as the outcome of greed, an external manifestation of internal chaos. In House of the Seasons, the fire shared the same motivation but had a different moral valence. Why? Because in this case, the patriarch of the family, knowing that the tofu factory cannot be split but that his poor daughter had to be provided for, did it out of a generous perhaps even self-sacrificing spirit, than out of greed.

Maybe that was the key difference. Or maybe it was something else. But in any case, one cannot but help reflect on the contrast between this wry, pragmatic grandfather — closer to the characters of Balzac’s novels than some stiff Confucian cutout — and the frigid, uncompromising patriarch as portrayed at the beginning of the movie. And maybe that’s the real moral lesson of the film: those who help and care about us the most are not necessarily those who make a big show of it. And to extend the analogy a little bit further: perhaps the social codes promising us authenticity or honesty are not as they appear.

Puritanism, after all, is the greatest hypocrisy of all.